Did Sandra kill Samuel in Anatomy of a Fall?

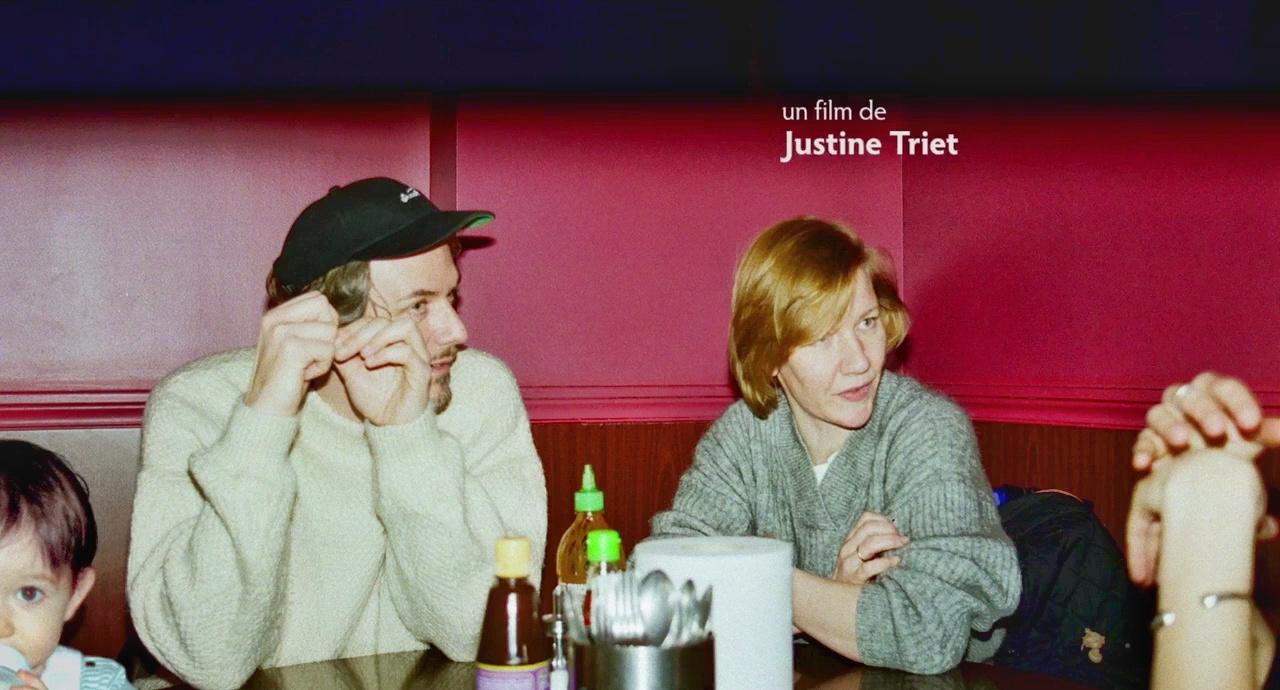

Directed by Justine Triet, Anatomy of a Fall is a critically acclaimed crime thriller that has garnered multiple prominent nominations and awards. The film follows the lives of Sandra Voyter (Sandra Hüller) and her son Daniel (Milo Machado-Graner) after the death of her husband, Samuel Maleski (Samuel Theis). Sandra becomes the primary suspect since she was the only person present at the house when Samuel fell to his death. What ensues is a gripping legal battle to uncover the truth about Samuel’s death. Was it accidental? Was it intentional? If so, whose intentions were behind it?

Co-written by Justine Triet and Arthur Harari, the film compels the audience to grapple with the elusive nature of truth. By presenting audio recordings, excerpts from Sandra’s novels, and other evidence, the filmmakers skillfully sow reasonable doubt. The prosecution accuses Sandra killed Samuel, either during a heated argument or with intent. Yet, these theories are soon contradicted by equally plausible evidence that supports Sandra’s innocence.

Anatomy of a Fall evokes the spirit of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950) and its iconic line: “It’s human to lie. Most of the time, we can’t even be honest with ourselves.” The film leaves the audience questioning the characters and their perceptions of guilt and truth.

Who took Samuel’s life?

Upon returning from his walk with Snoop, Daniel finds his father lying on the snow in a pool of his blood. Initially, Samuel’s death is believed to be the result of an accidental fall. However, when the autopsy report comes back inconclusive, every theory surrounding Samuel’s death seems just as plausible as the next.

Was it an accidental fall? The evidence supporting this theory begins to lose credibility when Sandra, the only person present during the incident, becomes a suspect. The prosecuting team’s strong argument draws suspicion toward her. They question how Sandra could have been asleep while loud music played repeatedly on the floor above. They theorize that during an argument, Sandra struck Samuel with a blunt object, which could also explain the three distinct blood splatters found in the shed. According to this theory, Samuel either lost his balance and fell or was pushed by Sandra.

This narrative that Sandra killed Samuel gains further weight with the discovery of an audio recording on Samuel’s USB key. Samuel had been recording random moments in his life as part of a new project. One of these recordings, captured the day before his death, featured a heated argument between him and Sandra.

In the recording, the couple blame each other for their shortcomings and refuse to acknowledge their own faults, we also discover that Sandra had cheated on Samuel. The audio ends with the sound of glass shattering and several thuds. At first, the thuds seem as if Sandra might have been hitting Samuel in a fit of frustration. However, Sandra later explains that the sounds were of Samuel hitting himself in the face. The film deftly plants and uproots doubts, with evidence that continually contradicts itself.

The defense presents an equally compelling theory that Samuel took his own life. Sandra recalls an incident six months before Samuel’s death, which she now believes, in hindsight, might have been a suicide attempt. She had noticed pills in Samuel’s vomit, but at the time, he refused to discuss it further. Her lawyer, Vincent Renzi, sheds light on Samuel’s struggles—the imbalance he felt in his marriage, his declining writing career, and the resentment he harboured toward his wife, a successful writer who had even plundered one of his ideas turning it into a novel. Vincent seeks to convince the jury that Samuel’s death was, in fact, a suicide.

Did Daniel Lie?

Daniel’s testimony holds significant weight in the trial, given his position as the child of both the victim and the suspect. He initially states that he heard his parents talking when he was leaving for a walk and insists they were not arguing. Daniel confidently asserts this because, at the time, he was walking under the window where the conversation was taking place. However, during a reenactment, his theory was disproven because of how loud the music was playing. In response, Daniel changes his statement, claiming he was inside the house, not outside under the window, to support his belief that his parents were not arguing.

Daniel’s credibility suffers, even with the prosecution’s argument that his memories might have weakened due to traumas. As a child, Daniel had an accident that permanently impaired his optical nerve, followed by a disruptive move to a different country. His childhood becomes even more fractured when he discovers his father lying lifeless and subsequently watches his mother being portrayed as a monster in the courtroom.

This trial forces Daniel to confront the reality that his parents are not the perfect figures he once imagined. He learns startling details about their lives, such as their therapists, medications, and Samuel’s first suicide attempt.

The court recalls Daniel to testify after he discovers new information relevant to the case. During the interim period, Daniel requests to stay alone in the house with Marge Berger. Daniel wanting to live away from his mother signifies guilt and shame, maybe he did believe that his mother was responsible for his father’s death.

While living alone, he conducts an experiment with Snoop that leads to a breakthrough. Observing Snoop’s behavior—excessive drinking of water and prolonged sleeping—Daniel concludes that Snoop may have ingested his father’s vomit which contained a lethal dose of asprin from his earlier suicide attempt.

Daniel also recounts a conversation he once had with his father about death. In hindsight, he realizes this conversation may have been Samuel’s way of preparing him for the possibility of his own death. However, we are presented with these partially fractured stories and moments from their lives, but there is no conclusive proof that they actually happened. Daniel could have easily fabricated the story to save his mother, his only parent from being convicted.

The Ambiguity of evidences

The question of whether Sandra killed Samuel cannot be boiled down to a simple yes or no. The filmmakers with the voice of characters have deliberately planted stories that may or may not have happened, and that may or may not have been altered for convenience. All these narratives lack witnesses or sufficient evidence. Even with ample proof that Samuel and Sandra were in an unhappy marriage, the evidence is not incriminating enough to definitively label Sandra a murderer. At the same time, it is not conclusive enough to exonerate her completely. The ambiguity of the evidence leaves the audience questioning the reality of the situation.

The prosecution quotes Sandra from one of her books: “My job is to cover the tracks, so fiction can destroy reality.” This statement casts doubt on her credibility. Sandra herself admits to lying about the bruises on her hand, claiming she was afraid it would put her under suspicion. Both she and Daniel are unreliable narrators, as they have been caught contradicting themselves throughout the trial.

To add to the uncertainty, both the prosecution and the defense present plausible theories to explain the blood splatter. While the prosecution argues that the blood splatter could only have been caused by Samuel being struck on the head with a blunt object—despite no such object being found at the crime scene—the defense contends that the splatter resulted from Samuel hitting his head on the shed during his fall.

The point of Anatomy of a fall

In the film’s opening scene, when Sandra is interviewed by a graduate, she remarks, “Your books always mix truth and fiction, and that makes us want to figure out which is which.” This quote serves as a subtle connection to the central theme of the film, reflecting the ambiguity of the narrative. As director Justine Triet noted in an interview, she intentionally avoided overexplaining, leaving the audience to grapple with the blurred lines between truth and fiction.

Ultimately, the film does not seek to provide a definitive answer but instead challenges the audience to confront their perceptions of guilt and innocence. It is a masterful exploration of the complexity of human relationships and the subjective nature of truth.